Section

5 Underwater explosion (shock)

5.1 General

5.1.1 There

are two principal loading mechanisms associated with the underwater

detonation of a conventional high explosive ordnance:

- shock wave loading;

- bubble flow loading.

5.1.2 The

energy released is in general, equally divided between shock wave

energy and the energy contained within the superheated high pressure

bubble of gaseous explosion products.

5.1.3 The

shock wave generated as the detonation wave passes into the water

is a highly non-linear pressure pulse which propagates at a speed

well in excess of the speed of sound in water (approximately 1500

m/s). However, within a few charge radii of the detonation point,

it can be mathematically defined as an acoustic pressure pulse travelling

at the speed of sound. Its amplitude falls off inversely with distance

and its profile can be characterised by a pulse which has an infinite

rise to a peak pressure followed by an exponential decay. The peak

value and decay rate at a given field point are given by the similitude

equations/coefficients for the explosive material.

5.1.4 In the

meantime, the gas bubble begins to expand against the ambient hydrostatic

pressure displacing water radially outward as incompressible flow.

As it expands, it loses pressure and temperature but the inertia of

the outwardly flowing water leads to an overshoot of the equilibrium

state so that at maximum bubble radius, the gas pressure is well below

the ambient. This initiates the collapse sequence, the gas bubble

is recompressed, slowly at first but then rapidly, to a minimum volume

by the hydrostatic forces. Because of the generation of a large pressure

in the bubble during this stage the bubble begins to expand again

and several other cycles may follow. The gas bubble and water interaction

can be thought of as a gas spring - mass system. It has a periodicity

associated with it but because of energy losses during the process,

the spring constant and mass changes over each cycle leading to a

change in the periodicity. At each minimum, that is, each recompression,

additional pressure pulses are emitted which become weaker with each

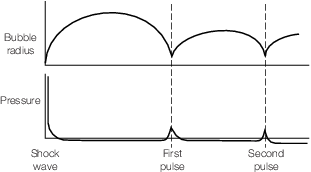

oscillation as shown in Figure 2.5.1 Shock wave bubble pulse.

Figure 2.5.1 Shock wave bubble pulse

5.1.5 The

bubble is pulsating in a gravitational field and will have a tendency

to migrate to the water/air boundary (the free surface). However,

this bodily motion of the bubble centre may be influenced by the proximity

of other boundaries such as the seabed or a nearby ship structure.

The rate at which a bubble will migrate to the free surface is a function

of the buoyancy forces generated when it is at its maxima and of the

drag forces it experiences as it moves through the water. Because

these drag forces are small when the bubble is at its minima, it tends

to migrate vertically upwards more rapidly when at its smallest volume.

5.1.6 The

fluid flow generated by the bubble dynamics is an important loading

mechanism for a structure, within its sphere of influence. Normally

bubble loading can be ignored if the bubble never approaches within

a distance of around ten times the maximum bubble radius. The important

feature of the bubble loading is its low frequency which is ideally

suited to induce ship hull girder flexural motion. This flexural motion

is commonly referred to as hull girder whipping. This loading mechanism

is dealt with in Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 6 Whipping. If

the bubble is within one bubble radius of the ship structure, it is

likely to form a jet which will impact on the structure. This bubble

collapse mechanism will cause extensive local damage. It is generally

not possible to efficiently design against this loading event for

a NS2 or NS3 ship. For a NS1 ship

there may be sufficient residual strength to withstand such damage,

but the extent of the damage will need to be determined by a specialist

calculation and the capability of the hull using a residual strength

assessment, see

Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 7 Residual strength.

5.1.7 The

shock wave loading is greatest at a point on the structure nearest

to the detonation event and because of the fall-off with distance

and the narrowness of the pulse width, it can be thought of as a local

loading event. (In contrast, the bubble induced whipping of the hull

girder is considered a global loading event.) The remainder of this

section will focus on the shock loading event only.

5.1.8 There

are no simple analytical or numerical techniques for reliably determining

the shock resistance of a structure. A measure of the resistance to

shock loading can be achieved by good design of the details of the

structure to avoid stress concentrations which may lead to rupture.

It is also possible to ensure that the plating thickness is matched

to the assumed performance of the joints using a simple damage law.

The inertial loads on the ship's structure caused by the equipment

and its seatings can be determined by time domain analysis.

5.1.9 The

shock performance of a ship's hull structure can be assessed solely

by conducting shock tests (usually at scale). However, cost usually

precludes this approach and a better strategy is to combine tests

to determine failure criteria with numerical modelling using Finite

Element methods. This complementary experiment /numerical simulation

approach reduces the amount of testing required and also provides

a method for extrapolating to full scale from scaled experiments.

5.1.10 Generally,

for a normal ship structure, the explosion required to cause uncontrollable

flooding or total loss of propulsive power or loss of mission system

effectiveness (radars, electronics, etc.) is much less than that required

to cause failure of a hull designed for normal sea loads.

5.1.11 Due

to operational requirements, some vessel types, such as minesweepers,

will be required to resist repeated shock loading at a specified level

without degradation of the system or structural performance. Such

vessels will also be expected to survive a single attack at a considerably

higher shock loading level.

5.2 Threat level determination

5.2.1 The

actual threat level used in the calculation of performance and the

areas of the ship to be protected by this design method are to be

specified by the Owner and will remain confidential to LR.

5.2.2 Loading

levels may be specified with varying degrees of structural and system

degradation to define the shock performance of the vessel. An important

consideration is the balance that has to be achieved between system

functionality and structural performance.

5.2.3 Two

performance bounds can be considered for the shock response of structure:

- The first performance bound (lower bound) relates to the onset

of material yield (assuming that careful design has ensured that no

buckling will occur before this state is reached). This level is useful

to know as it may have consequences for system functionality. For

example, there may be problems associated with equipment mis-alignment

because of the permanent set of the supporting structure.

- The second performance bound (upper bound) relates to removal

or rupture of material; this being the loading level at which there

is no longer sufficient residual hull girder strength to resist normal

environmental loading. This is addressed in a separate assessment

which is defined by the residual strength notations RSA1, RSA2 or RSA3 in Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 7 Residual strength. In conventional naval ships, this upper bound will be significantly

higher; but there will be little, if any, system functionality.

5.3 Notation assessment methodology

5.3.1 The

shock performance required is to be specified by the Owner and is

to include requirements for:

- Local strength assessment;

- Detailed design;

- Seat design, shock mounts and system hangers;

- Hull valve design and integration;

- Global strength assessment;

- Shock qualification/testing of equipment;

- 1st of class shock trial.

It is recommended that seats, valves, piping and equipment are categorised

into:

- equipment required to be capable of operation after the specified shock

event;

- equipment that is required to be captive, with reduced or no operational

capability after the specified shock event;

- equipment which has no requirements after the specified shock event.

See also

Vol 2, Pt 1, Ch 1, 3.1 Categories 3.1.1.

5.3.2 Ships

that comply with the minimum or enhanced requirements of this Section

will be eligible for the shock notation SH.

5.3.4 For

the minimum shock capability, the design emphasis should focus on

maintaining a high level of system functionality and reducing the

risk of flooding.

5.3.5 For

the assignment of the SH notation, the minimum requirement

is for the structure to be designed to resist normal environmental

loads in accordance with the Rules. For NS1 ships, the

inherent ruggedness in the Rules is sufficient for the structure to

resist a low level threat. For NS2 and NS3 ships,

the integrity of the hull plate and stiffeners is to be verified,

using the simple formulae for pressure in Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 5.4 Local strength assessment 5.4.1, and comparing the response

to a specified standard. In addition, the hull valves below the waterline

are to comply with the requirements of Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 5.8 Design guidance for hull valves, piping and seals.

5.3.7 In addition

to the analysis, the SH notation can be enhanced by selecting

detail design requirements to reduce the risk of fracture initiation

and structural collapse, based on historical work on shock. Details

are provided in Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 5.5 Detail design guidance.

5.3.8 The SH notation may be further enhanced by undertaking shock trials

in accordance with established procedures, on the first ship in the

class. The magnitude of the test is normally less than the design

value for the hull and at a level that is appropriate for the equipment

and systems.

5.3.9 Global

assessment may be undertaken for the SH notation, using

the residual strength procedures outlined in Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 7 Residual strength with the extent of damage being defined from the

results of the local strength assessment rather than the damage radii.

For the RSA1 procedure, the damaged structure is to be

removed from the analysis. For the RSA2 or RSA3 procedure,

if the damage is limited, the geometry of the damaged structure can

be modelled and if the damage is severe, the structure is to be removed

from the analysis. The structure is considered acceptable when the

hull girder is able to withstand the design loads as specified in Vol 1, Pt 5 Environmental Loads.

5.4 Local strength assessment

5.4.1 For

the notation SH, a simple analysis can be performed which

allows the motion response at any point in the ship to be determined.

This can be derived from experimental results or the Taylor plate

equations given below. Once the motion response is known, the damage

potential can be determined by comparing the response to a specified

standard.

Maximum velocity

|

V

max

|

= |

m/s m/s |

Time to maximum velocity

|

t

max

|

= |

seconds seconds |

where

|

z

|

= |

|

|

u

|

= |

|

|

θ |

= |

decay constant

of explosive charge in seconds |

|

P

m

|

= |

peak pressure in N/mm2

|

|

ρ |

= |

density of

water in kg/m3

|

|

c |

= |

speed of sound

in water in m/s |

|

m

|

= |

structural

mass per unit area in kg/m3.

|

5.4.2 A more

complex assessment method can be used to enhance the SH notation.

Methods can be used which accurately model the physics of the shock

event. At the simplest level, a finite element model of the structure

coupled with a suitable boundary element from proprietary software

may be used.

5.4.3 For

complex ships such as multi-hull designs a boundary element approach

may not be suitable and a volume element approach should be used.

Also, if non-linear fluid behaviour is important (i.e. hull cavitation

or bulk cavitation), then a volume element approach should be used,

unless the finite element or boundary element code used has a suitable

cavitation model.

5.4.4 The

assessment method or analysis used should be validated against shock

trial results and the evidence made available. As an alternative to

analysis, full or large-scale shock trials of a section of the ship

can be used to validate the proposed design. For novel design arrangements

or ship types, a combination of trials and analysis may be necessary,

the requirements of which will depend on the threat level and type

of structure or ship design.

5.4.5 Any

finite element analysis performed for local strength assessment is

to be in accordance with the requirement of this Section for assignment

of the SH notation.

5.4.6 The

extent of the analysis model is to be from about 0,35L

R to 0,55L

R and encompass at least two

major compartments and three watertight bulkheads. It is to be sufficiently

large to avoid reflections within the structure from the boundaries,

for the threats considered. For the assessment of structural strength,

the structure need only be modelled to 1,0 m above the design water

line. If the model is to be used to determine equipment response,

all structure within that section should be modelled.

5.4.7 The

model, or versions of the model, should encompass representative integral

tank arrangements and hull penetrations, stabiliser inserts, hull

valves, the failure of which could lead to uncontrollable flooding.

Penetrations, the failure of which will not lead to significant flooding

or damage, need not be considered. The tanks and penetrations need

not actually be in the section under consideration but should be sufficiently

similar to represent structure outside the region modelled.

5.4.8 All

masses above 100 kg should be included in the model together with

an approximation of the mounting system if applicable.

5.4.9 The

model should include at least one major machinery item or raft.

5.4.10 The

response of hull panels depends upon a large number of variables which

are both design and attack geometry dependent. To simplify the task,

the following assumptions can be made:

- The charge detonates in the worst location, perpendicular to the

structure under consideration.

- All welding is continuous and there are no manufacturing or material

defects in the panels.

5.4.11 During

the analysis, appropriate elements are to be used to couple the fluid

medium and the structural model.

5.4.12 The

shock wave can be represented by an exponentially decaying, infinite

rise time pressure pulse which sweeps across the structure at the

speed of sound.

5.4.13 Non-linear

structural modelling can be used in finite element analyses. If used,

stiffeners should be modelled explicitly using shell elements of the

appropriate thickness. Stiffener flanges should be modelled with at

least two elements per half width or flange. Initial imperfections

in the hull plating are to be taken into account prior to the dynamic

loading analysis.

5.4.14 The

structure is considered acceptable when:

- Elastic deflections are less than the temporary limits of machinery

and systems.

- Permanent deflections are less than the limits of machinery and

systems.

- Deflections and strain are less than the limits of the structure

or applicability of the analysis method.

5.5 Detail design guidance

5.5.1 For

enhanced shock performance, any of the following design details can

be included in the design, which is based on historical shock testing

and experience.

5.5.2 Tank

boundaries are to be of equivalent scantlings to the hull boundaries.

5.5.3 Intermittent

welding is not to be used on hull girder structure or tank boundaries

below the water line or for 1 metre in way of the deck and shell connections.

5.5.4 Structural

discontinuities are to be avoided and in general a minimum taper of

1:4 is to be applied to changes of structural section.

5.5.5 Bar

keels are not to be fitted.

5.5.6 Tanks are to be integral with the ship's structure. For free standing tanks

greater than 100 litres, calculations demonstrating the capability of the tank and

supporting structure are to be submitted.

5.5.8 The

size of longitudinal members passing through, or ending on, bulkheads

are to be as small as possible, though still complying with the appropriate

scantling requirements of Vol 1, Pt 6, Ch 3 Scantling Determination. Bulkhead stiffeners are to be fitted perpendicular to

the shell plating.

5.5.9 Where

deep longitudinal members are unavoidable, their connection to the

bulkhead will be specially considered.

5.5.10 Bottom

longitudinals are to be of a uniform size. Alternate large and small

longitudinals are to be avoided as they may lead to high shear forces

in the bulkhead.

5.5.11 Access

holes in all primary framing members are to be avoided in areas of

high shear stress. Where they are essential to the operation of the

ship they are to be circular and fitted with appropriate stiffening

or compensation.

5.5.12 Frames

on the bilge are to be provided with adequate lateral support, consideration

should be given to the fitting of a shock stringer.

5.5.13 Lapped

connections are not to be used to connect frames to floors.

5.5.15 In

transversely framed ships, bulkhead stiffeners are to be terminated

on a shock stiffener welded to the bulkhead, parallel to, and spaced

500 mm from the shell. The bulkhead plating thickness is to be suitably

increased in way. The shock stringer and bulkhead plate may be replaced

by a web frame of suitable scantlings.

5.5.16 Bulkhead

penetrations are to be grouped, away from the side shell and kept

above the water line as far as is practicable.

5.5.17 Shell

frames and deck beams are to be fitted in such a way as to minimise

misalignment. Brackets where fitted are to be radiused and fitted

with soft toes.

5.5.18 Where

the vessel is to be subjected to very high levels of shock, the following

details can be included in the design.

5.5.19 Pillar

bulkheads are to be used below the waterline in place of pillars.

5.5.20 It

is recommended that symmetric stiffeners should be fitted to the to

the underwater portion of the shell envelope.

5.5.21 Where

a transverse framing system is used, the shock capability of the structure

will be specially considered. Calculations supporting the use of particular

design details are to be submitted.

5.5.22 All

bulkhead stiffeners are to end on longitudinals, see

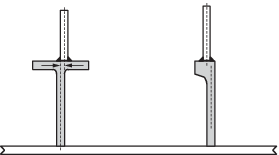

Figure 2.5.2 Bulkhead stiffening. An increased thickness

margin strake on bulkheads of thickness not less than 80 per cent

of the adjacent shell plate thickness, the thickness of the adjacent

shell stiffener or 6,5 mm. The margin plate is to have a width not

less than 1,5 times the adjacent stiffener spacing or four times the

depth of adjacent shell stiffeners.

5.5.24 Where

brackets are fitted, similar tolerances to Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 5.6 Seat design 5.6.5 are to be applied subject

to a suitable area being provided for weld fillet, see

Figure 2.5.3 Bracket connections. Tripping brackets or

intercostal stiffeners should be used to stabilise the frame at the

bracket toes. Brackets are to be radiused and fitted with soft toes.

Figure 2.5.3 Bracket connections

5.5.25 The

cross-sectional area of the bulkhead stiffeners at their outer ends

in way of the margin plate should not be less than 60 per cent of

the area of the web of the hull longitudinals to which they are attached.

To achieve this requirement, the bulkhead stiffeners may be tapered

between the outer end and the point at which the size is the minimum

required to withstand lateral pressure. The slope of the taper is

to be such that:

Ax > 0,6AL- 2tx/3

where

|

A

x

|

= |

cross-sectional area of the bulkhead stiffener at a distance

x from its outer end |

|

A

L

|

= |

web area of the longitudinal, and t is the bulkhead plating

thickness at x. |

5.5.26 The

short stiffeners above the turn of bilge should be on the same side

of the bulkhead as the main bulkhead stiffeners and should end on

such a stiffener, see

Figure 2.5.2 Bulkhead stiffening. Where necessary, an additional diagonal stiffener may

be worked to facilitate the arrangement.

5.6 Seat design

5.6.1 The

shock notation may be enhanced by specifying that some or all of the

equipment seating is to be designed to resist shock loading. Seat

design should take account of the acceleration and deceleration from

the shock wave; the magnitude of the shock acceleration will depend

on the equipment mass, position in the ship and mounting arrangements.

The seat design methodology is to be in accordance with a specified

standard. The selection of seats to be assessed will depend on the

equipment supported and the compartment in which it is situated.

5.6.2 Minor

seats should be assessed to ensure that equipment remains captive.

Detail design requirements such as minimum thickness, alignment, and

free edge support can be specified to improve shock performance. In

the absence of information, minor seats can be considered as those

with equipment mass below 100 kg.

5.6.3 Seats

which are not classed as minor are to be assessed for shock loads

using acceleration values appropriate to the region of the ship in

which the equipment is installed. Large items of equipment where the

seat is integrated into the ship’s structure will normally require

a finite element analysis to assess the strength of the seat. Where

these seats are adjacent to the hull or an integrated tank, the fluid

structure interaction may need to be modelled. See

Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 5.4 Local strength assessment.

5.6.4 The

shock accelerations are to be specified by the Owner. In general,

accelerations will be specified for the following regions of the ship:

-

within 2,0 m of

the wetted hull;

-

main transverse

bulkheads and decks below the strength deck;

-

above strength

deck and superstructures.

Shock accelerations can be scaled using a factor for different

equipment based on its category of use.

5.6.5 For

each equipment seat to be assessed, a report is to be provided containing

the following information:

-

equipment mass

and centre of gravity;

-

location in vessel;

-

mounting system;

-

spatial clearances

around the mounted equipment;

-

captivity requirements;

-

relevant excitation

frequencies from mounted equipment in the case of reciprocating or

rotational machinery;

-

calculations demonstrating

maximum stress and displacement, under vertical acceleration, vertical

deceleration and athwartships accelerations. For non-linear analyses,

strain rates are to be provided;

-

equipment alignment

requirements, as appropriate.

5.6.6 As a

minimum, the following seat load cases are to be assessed:

-

bolts; pull through,

tensile, shear and bearing strength;

-

seat flange; flange

bending and top plate weld area;

-

seat web; buckling

and overturning;

-

deck; seat weld

area if less than flange.

5.6.7 Stress and strain are to be assessed against criteria appropriate for the

seat material and loading rate. The first fundamental mode of vibration of the seat

including equipment is to be greater than 10 times the shock mount rated natural

frequency to provide a sufficiently rigid base for the shock mount. In the absence of

specific information, for steel, the data in Table 2.5.1 Allowable stresses for seat

design may

be used:

Table 2.5.1 Allowable stresses for seat

design

|

|

Tension

|

Bending

|

Shear

|

| Plastic deformation of seats

|

1,3 σps

|

1,3 σps

|

1,0 σps

|

| Long loading times ≥5 ms (elastic deformation

only)

|

1,0 σps

|

1,0 σps

|

0,8 σps

|

| Short loading times <5 ms

(elastic deformation only)

|

1,2 σps

|

1,5 σps

|

0,9 σps

|

where

|

σps

|

= |

static 0,1% proof stress |

The values in this Table are applicable to mild and high tensile steel

grades up to a yield strength of 400MPa.

|

5.7 Shock mounts

5.7.1 All

shock mounts are to be of an approved type. Approval is to be undertaken

by organisations approved by the Naval Administration. Approval documentation

should contain the following information in accordance with NATO document

ANEP63:

-

nature and application

of the mount, including generic type, application, load range, shock

displacement, environmental constraints and frequency range;

-

description of

the mount assembly, including the complete assembly, the mount and

the associated components;

-

details of the

mount standard assembly and installation;

-

physical size,

mass and dimensions;

-

performance data

as listed in Table 2.5.2 Shock mount

characterisation;

-

details of the

mount testing process, including method of force generation, number

of mounts used/shots used, mount supplier, validation, mount permanent

deflection, details of test facility and date of testing;

-

mount specific

protection, installation, inspection and maintenance requirements;

-

any applicable

historic data, i.e. changes to the mount details over time. For example,

changes of material, etc.

Table 2.5.2 Shock mount

characterisation

| Mount

size number

|

|

1

|

| Nominal

load

|

kg

|

|

| Static stiffness

|

- Vertical V

- Horizontal H

A

- Horizontal H

R

|

|

|

| Dynamic stiffness

|

- Vertical V

- Horizontal H

A

- Horizontal H

R

|

|

|

| % of

critical damping

|

| Vertical

static displacement at nominal load

|

mm

|

|

| Natural frequencies

|

- Vertical V

Horizontal H

A

Horizontal H

R

|

|

|

| Dynamic

magnification at resonance

|

–

|

|

| Shock displacement capacity

|

- Vertical V

- Horizontal H

A

- Horizontal H

R

|

|

|

| Maximum transmitted acceleration at

nominal load

|

- Vertical V

- Horizontal H

A

- Horizontal H

R

|

|

|

| Range of

validity of mount surface/best fit governing equation (where applicable)

relative to unloaded condition

|

±mm

|

|

| Required

support stiffness

|

N/m

|

|

| Required

support strength

|

N

|

|

5.8 Design guidance for hull valves, piping and seals

5.8.1 Hull

valves below the waterline are to be of an approved type. Approval

is to be undertaken by organisations approved by the Naval Administration.

Approval documentation should contain the following:

-

details of the

valve body, main components and securing arrangement to the hull,

including bolt material grade and tightening torque;

-

details of the

valve testing process, including method of force generation, number

of tests, validation, details of test facility and date of testing.

5.8.2 Only

materials with sufficient ductility to avoid fracture under shock

conditions are to be used. Materials should be able to withstand high

stresses for very short periods without exhibiting brittleness. Valve

bodies are not to be made from materials with an elongation of less

than 10 per cent. There should be adequate material in way of the

valve seat to prevent distortion.

5.8.3 In general,

the valve body should be as symmetrical as possible with no rapid

changes in section; web stiffeners should not be incorporated. Spindles

should be as short as possible. Square threads or sharp thread run-outs

are to be avoided. Handwheels should be as light and small as possible.

5.8.4 The

weight of the actuator is to be considered in the design of the valve

and its connection to the hull. The actuator can form a considerable

proportion of the overall weight of the valve.

5.8.5 Consideration

should be given to the attached piping and its capacity to withstand

shock:

-

Detachable pipe

connections should be kept to the minimum necessary for installation

and maintenance requirements;

-

Flanged and welded

connections are to be used adjacent to the hull valve. Adjacent piping

is to be designed to allow the valve and hull to flex under shock

with limited restraint;

-

Where necessary,

piping shall be supported with shock resistant mounts at a sufficient

number of locations commensurate with the design shock level. The

selection of shock mounts should consider displacement capability, see

Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 5.7 Shock mounts. The response

of the piping relative to equipment should be considered. Sufficient

space between equipment and piping should be provided to ensure they

do not contact each other in a shock scenario;

-

The routing of

piping should be developed to minimise the number and size of penetrations

through bulkheads, see

Vol 1, Pt 4, Ch 2, 5.8 Design guidance for hull valves, piping and seals 5.8.11;

-

The consequences

of leakage from piping and fittings should be investigated;

-

Brackets should

not be welded direct to steel piping;

-

Adequate division

of vital piping systems to isolate damage should be considered;

-

The shock resistance

of flanged connections should consider bolt preload, anti-rotational

locking devices where appropriate and performance of gaskets.

5.8.6 The

sealing arrangement between the valve and the hull insert is to be

suitable for shock loading and able to accommodate elongation of the

securing studs.

5.8.7 Hull

valve designs can be approved by the following methods:

-

physical testing;

-

semi-empirical

methods;

-

direct calculation.

5.8.8 Physical

shock testing may be used to assess the valve. Physical testing is

to take account of the attachment to the hull and possible combinations

of hull scantlings, stiffener spacing, materials, etc.

5.8.9 Recognised

semi-empirical methods may be used to assess the valve.

5.8.10 Validated

numerical methods may be used to assess the valve. Where used, they

are to take account of the following criteria:

-

asymmetry in

the valve and piping assembly;

-

dimensions of

the hull insert/pad;

-

use of sea tube

between the valve and hull insert;

-

hull scantlings

and stiffener/frame spacing;

-

plasticity in

the hull and valve assembly;

-

the effective

mass of the valve, actuator and piping;

-

the valve to

hull securing arrangement, taking into account fit and pre-stress

effects;

-

dynamic properties

of materials;

-

the effect of

any surrounding equipment or masses.

Sea tubes of unusual material, GRE for example, or unusual configuration

are to be assessed by physical shock testing and not assessed by numerical

simulation.

5.8.11 The

potential for leakage from seals/glands under shock loading, and the

consequences of leakage, are to be considered. The shock resistance

of vital seals/glands, including stern-tube seals, is to be validated

by shock qualification testing. The sealing efficiency of stern-tube

seals should not be compromised by the anticipated axial, radial and

angular shaft movements commensurate with the design shock level.

|